Australia and New Zealand are a long way from almost everywhere except, perhaps, China. That makes them vulnerable: “The industry has a high exposure to import penetration, which contributes to over half the domestic demand,” say market analysts Ibis World, in a report dated September 2020. Which is another way of saying that imported cranes take 62.5% of the domestic market. Add shortages of skilled labour, and the high cost of all labour, and makers of hoists and cranes in Australia and New Zealand might seem to have the odds stacked against them.

Even so, the Ibis report tells us that the number of businesses in the Overhead Crane Manufacturing industry in Australia has remained steady over the past five years. And this despite Covid, which of course has not helped: “The COVID-19 outbreak and subsequent economic recession are likely to moderately affect the Overhead Crane Manufacturing industry. Industry operators are likely to face weak demand from the manufacturing, mining and building construction markets,” – mining of course is a major consumer of lifting equipment in Australia – “but it may derive some stimulus from infrastructure construction,” says the same source.

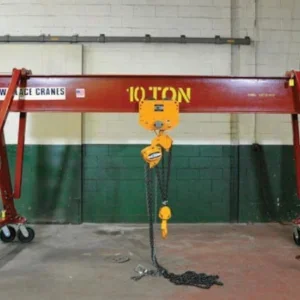

It may indeed. Australia in particular has some impressively large infrastructure projects right now, driven by the huge, almost explosive, growth of their cities. Sydney, the most populous city, with currently around 5.3 million inhabitants, is forecast to reach 6 million by 2026; Melbourne, currently Australia’s second city with 5.1 million, is growing even faster and by that time is forecast to overtake with 6.2 million people. The Australian Bureau of Statistics say by 2050 Sydney will be a city of 9.08 million and Melbourne 9.61 million. Both cities have embarked on very ambitious, and long-overdue, expansions to their metro systems, which in both cases have been not far short of rudimentary, and both of which involve tunnelling under the central business districts – and in Sydney’s case under the iconic harbour as well – as well as expansions into the suburbs. Brisbane, too, has Queensland’s largest infrastructure project in the form of the Cross River Rail, 10 km of rail line including twin tunnels under the Brisbane river and the business district. All of these are of course big users of lifting gear. The major player Eilbeck, for example, has constructed and commissioned for the Melbourne project three tunnel works cranes for early works, plus 500t and 250t Full Portal Cranes for lifting the tunnel boring machines at the West Gate portal to the tunnelling works, as well as six large gantry cranes for the yard supplying the concrete tunnel lining segments. These latter are two 10 (5+5) t x 22m span overhead cranes, two 10 (5+5) t x 7.6m semi portal cranes, and two full portal cranes. They supplied another 18 cranes for the Sydney metro project.

James Schmidt is engineering manager of Sam Technology, part of the Schmidt & Muller Group based in New South Wales. It supplies gantry cranes for aluminium, steel and paper plants and equipment to aviation and the mining industry. “Mining, defence, and infrastructure seem to keep on going,” he says. “China and Korea import a lot, and it is changing from the days when they were cheap and cheerful and poorly made. Now the European manufacturers are making things there, and their products are perfectly acceptable. At the end of the day a crane is something that goes up and down and as long as it does that the customer is reasonably happy.

Which obviously leaves a problem for local manufacturers such as Sam Technology: “We get involved in the more heavily engineered side – that’s the only way we are going to survive.”

They clearly do survive, and even weathered the pandemic successfully. “The pandemic was not as disruptive as I thought it would be” says. Schmidt. “It has not been that flattening, and everyone seems busy.” It has not had to furlough staff, or lay anyone off. Instead, it is facing the reverse difficulty. “Our main problem is getting the personnel. Australia isn’t importing people any more.’

It is the same for the smaller companies as well. “Business is booming, everyone is busy,” says Bruce McKay, director, Global Track. “That’s the way it has been during the big lockdown times and after.”

Based in Geelong, Victoria, Global Track could be said to typify the independent, go-it-alone entrepreneurial side of Australian business. It is not quite a one-man outfit, “I have a guy who helps me, he has his own business as well,” says McKay, “and I have an apprentice. I sell Kito equipment and we make hoists, mostly light rail gantry systems for people doing light to medium engineering; there’s less paperwork when you stick to the light stuff. I pass the big-capacity inquiries on to JDN.” JDN Monocrane, also based in Victoria, has around 17% of the Australian heavy hoist market.

“My customers are a bit scattered,” says McKay. “At the moment I am doing a job for agricultural equipment makers; they make sprayers and that kind of thing. There’s another job for AKD Softwoods, who are big in Australia; and at Ford, who withdrew from making cars in Australia some years back but kept a development plant not far from here when they shut down the big one. They have a testing track at Geelong which I supply.

“Life is not too bad, at the moment. Since Covid came along the government has put a lot of subsidies into business. It waived the quarterly tax bill, to pump money into the economy and business; and brought in a Jobkeeper scheme to help affected businesses: if your turnover has gone down by 30% or more they give you A$1500 every two weeks for every person you employ, to help cover their wages. It has stopped now. The last payment was at the end of March; but it kept people going. Plus, there was a A$10,000 subsidy to all companies that qualified; for me, that was a Godsend. I still had work coming in, I was quite lucky to be getting the Jobkeeper money – most months I just crept past the qualifying barrier by a few percent. That lasted for a year, and as I say it really did help. So, from the point of view of small businesses like mine the government handled the pandemic reasonably well.”

There may be long-term consequences for his business, though: “Melbourne had a very long lockdown,” he says. [At the time of writing, (early June) a lockdown extension was on the cards.] “I am in regional Victoria – that is outside the Melbourne area – where we were allowed to travel. But they closed the South Australia border, which meant I couldn’t go there to do the installation work for a good and regular customer there, who makes solar panels. So, I supplied the hoist and the gantry equipment and he installed it himself. And when he discovered how easy it was to install, on the next order he said; ‘I will do the easy parts, the installation, you just supply me with the parts.” He has had dozens of cranes and installations from me in the past. From now on it looks like it will just be the cranes.”

So, in Australia the pandemic disruption is evolving into business as usual, if a slightly different business model.

It is a similar story in New Zealand. “Baker Cranes has been busy since coming out of Level 3 lockdown in April of last year,” said Ralph Bacon, project administrator of Baker Cranes. “We believe most of the other crane manufacturers in NZ are reasonably busy also. The market is small by international standards but it is quite competitive, and there is a range of crane suppliers, from those importing whole cranes from third world countries to those such as ourselves, who import components and manufacture steelwork here. Imported cheap hoists are not too much of a problem as a significant proportion of customers seem to feel more comfortable with established brands, especially the European ones.”

Which is where Baker fits in: “Baker Cranes has been supplying cranes for 30 years, and for 20 of those we have been the NZ agent for ABUS Crane Systems. We design in-house, we manufacture steelwork in-house, and we carry out the installation and servicing, and because we have a reputable European agency as well, we believe this gives us a competitive advantage over most of the other suppliers. One other advantage we have is our relationship with Eilbeck Cranes in Australia, as we purchase our components via them. This relationship has allowed us to leverage their knowledge and processes to improve our own methods.

“Obviously New Zealand is a long way from Germany,” he says, “so our lead times are dominated by the shipping time. Sometimes this can be a problem but in most cases we manage deliveries to suit the customer. However, the recent shipping turmoil has not helped.”

Shipping turmoil, long distances, pandemics, cheaper cranes from Asia – what else would you have to add for a perfect storm? But hoist makers in Australasia seem to keep on going, happily and even optimistically.

The place is booming, and you have to admire their resilience.