Tiny even by European measures, Baltic states have similar political histories. After about 50 years of Soviet domination – or “occupation,” as local politicians refer to this period – Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia set a course toward European integration. They spent the 1990s working hard to reorient their political and economic systems from East to West. Now their doggedness has been rewarded, and all of them are joining the European Union.

Privatisation, currency stabilisation and encouraging foreign investment were early priorities in all three Baltic states. They diversified their economies and became less dependent on transit cargo flows from and into Russia and other former Soviet republics. Manufacturing enterprises benefiting from restructuring and injections of foreign capital succeeded in increasing exports to Scandinavia and other EU countries. Estonia, the smallest and liberal of the three, led the trend and showed the highest economic growth rates in the region until 2002. But in the last two years the bigger Lithuanian and Latvian economies outran Estonian in terms of growth and foreign investment.

The Baltic countries are now adjusting their commercial and technical standards to match those of their western neighbours. For example, Estonia and Latvia have enacted legislation banning imports of of industrial equipment that doesn’t meet European safety standards. Lithuania will have to follow suit shortly. Interestingly, it is the adoption of EU requirements that compels the Baltic states to introduce some restrictions on their extremely liberal trade policy.

All three Baltic countries strengthened cooperation with one another after regaining independence. Other magnets have also been at work. The Estonians, who are ethnically and linguistically close to the Finns, built very good political and business relations with Finland – just 2-hour boat trip away.

Russia has lost its dominance as a trade partner in the region, though it remains the largest supplier of oil and gas to Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania and a main customer of most local ports. The 1998 financial crisis in Russia affected Baltic economies, but also accelerated the region’s reorientation toward the West.

Time is on the side of Western crane dealers in the Baltics. Just be patient and the old cranes, inherited from the Soviet era, will tumble down. Russian and Ukrainian crane makers lost their monopoly in Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia shortly after the three tiny nations regained their independence in 1991. Last year, Estonia and Latvia banned the import of cranes that don’t meet European safety requirements, which means their markets are now completely closed to cranes from Russia, Ukraine or Bulgaria. But even before this ban, almost no Russian or Ukrainian cranes were delivered here due to collapse of economic ties among post-Soviet states and new trade barriers.

According to data provided by the Technical Control Center, an Estonian government agency supervising industrial safety, the total number of cranes registered in Estonia in 2003, amounted to 1,850, including 730 overhead travelling cranes and hoists and 154 gantry cranes. In Latvia, 6,123 cranes and hoists with a capacity of 1 tonne or more were registered as of January 2004, the State Labour Inspectorate said. Officials did not provide a breakdown by type of cranes. The Lithuanian Labor Inspectorate did not respond to repeated requests for crane statistics.

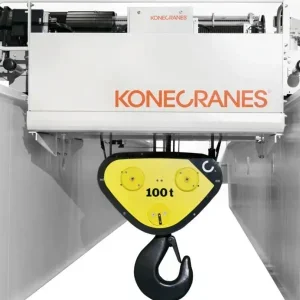

Since the early 1990s, Konecranes established subsidiaries that sell cranes and provide repair and maintenance services in all three countries. It has supplied over 100 cranes and hoists to Estonia, the company’s representative in that country, Peter Alajaan, said. The company’s major customers in Estonia include shipyards in Tallinn and Loksa. Konecranes has about 60-70 percent of the Estonian crane market share, Alajaan estimates.

Boris Sokerjanskis, head of the company’s Riga office, estimates the number of cranes and hoists supplied by Konecranes in Latvia at about 40.

The Lithuanian market is still open for companies selling products without EU certificates. In Lithuania, Konecranes competes not only with the usual rivals such as German crane makers Demag or Abus, but also with Russian and Bulgarian crane makers like Baltkran and Podem, which offer lower prices. Director of Konecranes’ Lithuanian subsidiary, Jonas Paulikas, cited the following contracts as the most significant: the supply of two STS and two RTG cranes to KLASCO, delivery of six cranes to the Western Shipyard in Klaipeda, two 2t overhead travelling cranes supplied to the Ignalina nuclear power plant and the modernization of its 50t overhead travelling crane, and the supply and installation of four overhead travelling cranes with capacities from 3.2t to 8t to the Lithuanian plant of the Finnish Rannila company.

Western crane makers already are taking advantage of a cheap skilled work force and an attractive investment climate in the Baltics for producing cranes or at least metal structures for them locally.

There are several crane makers in Lithuania, created on the base of former repair plants. They produce metal structures and assemble cranes and hoists, using parts from German, Norwegian and Bulgarian companies.

The Mechanika plant in the city of Siauliai is now the biggest crane producer in Lithuania. In the Soviet era Mechanika annually produced about 30 gantry cranes but nearly suspended production due to a lack of orders in the early 1990s, the company’s director Vaclavas Ramonas said. The enterpise got a second wind in 2000, when it established a joint venture with Norway’s Munck Cranes and its subsidiary Dreggen Crane to produce single- and double- girder cranes and deck cranes. In 2003, Mechanika made about 50 cranes, half of which were deck cranes produced on licence from Dreggen Crane.

Mazeikiai Strele, in the town Maizeikia, produces hoists, using parts from Germany’s Abus and Bulgaria’s Podem. Hoists with 3t to 10t (9 US ton) capacity are the most popular models, the company’s director Gestutis Slavinskas said. Maizeikiai Strele also makes ropes and chains for lifting mechanisms, and rents tower and mobile cranes. Leasing brings about half of the company’s annual revenue totaling six million lits (about two million euros). The company also provides repair and maintenance services.

Vilniaus Kranai produces overhead travelling and gantry cranes with capacities up to 20 tonnes, using components from Demag.

Konecranes is now looking into the possibility of localising production of metal structures and other parts for cranes it supplies to Lithuania, company officials said.