They come with different names: hand chain hoist, chain block, chain fall, block and tackle; or lever hoist, lever block hoist, ratchet hoist, Come-Along, Pul-lift (which is a trademark of Yale, and should be used only for their products but frequently isn’t, in the same way as Hoover has become a generic name for Vacuum cleaner.) The first group all describe the same thing: a device where you pull on an endless chain which makes another endless chain lift the load. The second group describes a device where you pull up and down, or side to side, on a rachet lever, which in turn raises the load chain. Both sets are worked by human muscle.

Electric power, battery power, hydraulic power, pneumatic power… All have been and are used to supply energy for hoists, and all of them are useful and time-saving and convenient and efficient – in their place. Do they still leave a place for the man- or woman-powered chain hoist – or is that as dead as the dodo, old-fashioned, yesterday’s tech, no longer needed in the all-singing, digital mechanised brave new world of now? Have we grown lazy, or should we use our own muscles more – or is that injurious to health, to safety and to the well-being of the people who are charged with moving objects from A to B in a factory or warehouse or place of employment?

Should one then opt for a powered hoist or a manual one? There are places where manpower is still the best option – and some of them are unexpected. Perhaps surprisingly, the weight of the load is not the limiting factor. The force with which anyone can pull down on a chain is obviously limited. (Just for starters you cannot usefully exert a downward force greater than your body-weight, because if you did the chain would stay still and your feet would leave the ground. Say that twothirds of your body weight is the maximum downward pull that an average human being can reasonably exert; the average body-weight of a European male is around 85kg. I leave the reader to do the sum.)

But chain hoists come with a built-in mechanical advantage which can multiply the exerted force many times to lift a heavier load. (The mechanical advantage can come from both the gearing ratios inside the block, and the number of chain falls – ie how many strands of chain support the hook.) Remarkably, there are manual chain hoists available which can lift 100 tons, by manpower alone.

On-line suppliers Lifting Safety offer one, available by special order, and it looks a monster. Hoists with marginally-more modest 50-ton capacities are standard and more widely available. Yale has its VSIII range, which comes in capacities from 750kg up to the aforementioned 50t; in that version it has 18 falls of load chain and a lift height of three metres.

Tiger, which has a speciality in subsea lifting, has a 30-ton-capacity manual chain hoist specially designed to lift ROVs (Remotely Operated (underwater) vehicles – unmanned yellow submarines to the outside world) from the water. It has twin heads and 10 falls; a new feature is a hand-wheel for making fine adjustments to the height of the ROV when it is safely on deck.

William Hackett offers its C4 Hand Chain Block C4-CHCB-3866, which in the highcapacity 50 ton version has 20 chain falls.

It is not easy to imagine who would want to raise a 50 ton weight by hand, unless you were an early man building the pyramids or Stonehenge; but there is a demand.

“We have them available off the shelf,” says Josh Burgess, director of Operations, William Hackett, “and they do sell.” Who buys them? “Mainly the energy industries” he says. “There are places where an electricity or hydraulic supply is not easy to install. The underside of an oil rig might be an example. But these are heavy beasts in themselves – they weigh upwards of a ton, so installing them is not to be taken lightly.

“There are 20 falls of chain in our 50t manual chain hoist, meaning there are 10 sheaves that the load chain gets pulled around. This mechanical advantage essentially suggests that it should take the same effort to operate a 50t hoist as it does a 5t hoist. This is not 100% accurate though,” – factors such as increased friction come into play – “and I have been advised that the effort required to operate a 50t hoist is approximately 500N.”

More than one operator pulling on the chain would seem essential.

Nothing comes for free, however. The downside of such high mechanical advantage is that the speed of your lifting is very much reduced – by the same ratio as the mechanical advantage, as Archimedes worked out around the year 250 BC.

Raising a 50t load by hand by even a metre would be a very slow business indeed – which accounts for the lift height of just three metres of the Yale version we mentioned above.

These very-high capacities of chain hoists are, let’s face it, not common. Most applications where 50-ton loads need moving, even occasionally, would find a powered solution more efficient.

If the load is of the order of 250kg to a few tons, and if portability for use in remote sites is important, then the manual chain hoist, and its close relation the lever hoist, come into their own.

So down mine excavations, or up on overhead wires, an engineer might well want to carry his hoist with him on his belt or in a toolbox, attach it to some suitable support at his worksite, and then use it to lift a component for repair or manoeuvre it into position. The phrase ‘pocket winch’ for the ultra-lightweight and small lifting aid has not until now been coined, but perhaps it should be. Thus, Yale has its Mini 360, which fits the brief exactly.

It is a compact design, the smallest of its hand chain hoists, and can fit in any toolbox. For lightness, the housing is of aluminium. The low weight promotes, they say, countless possible applications, such as assembly work in industry, car repair shops, crafts and so on. All the internal parts are protected, so the device is fit for use outdoors or in rough environments. It comes in capacities of 250kg and 500kg.

The load pressure brake complies with all technical regulations and therefore holds the load in any position.

The hand chain guide has a special feature: it rotates, through 360. This allows the operator to pull from any angle. As well as convenience it means that he can stand clear of the load and the danger zone, even in confined and tight spaces. The device is an all-rounder, able to be used for horizontal pulling as well as vertical lifting. Standard equipment includes forged lifting and load hooks made from age-resistant high-alloy tempered steel, which for safety gradually open when overloaded rather than breaking. The hooks can be rotated through 360 and are fitted with robust safety catches.

Tiger too has a Mini range, available in both chain block and lever hoist variants; the lever hoist makes its intended applications, for on-site repair and maintenance work, crystal clear by being supplied with a belt bag, so that it can be carried hands-free round the operator’s waist.

Kito is also in that niche. Its CX010 hand chain block is designed to be easy to carry, easy to handle, and to fit in tight spaces – and to be extremely light weight, despite its load capacity of 1,000kg. Suggested applications are repair, assembly or maintenance work.

Kito says the product is answering a great demand for compact hand chain blocks. “Almost all users choose a hand chain block for mobile applications by two criteria, the dead weight and the load capacity,” says the company, “because you need as little weight as possible and as much power as possible at the same time. On this account, the small and compact Kito CX is available in three different versions. The Kito CX010, weights 7.3 kg and has a load capacity of 1 ton, offering application with heavy loads. 250 kg and 500 kg capacities are others in the range.

On all three models the housing is compact and made of aluminium. Inside the housing is high-quality, two-stage precision gearing. A heat-treated steel frame serves as a stable bearing for the gearwheels; the gearwheels themselves are cold forged for maximum and constant performance. The chain sprocket casting is precisely matched to the gearbox so that the nickel-plated load chain is carried flawlessly. The intent has been for a small but strong construction.

And the CX010 has an unusual feature. As small hand chain blocks are often transported and used in several places, it is provided with a ‘Twist Checker’ as part of the standard equipment. It is a small tool that determines quickly and easily if the load chain is twisted or if the hoist can be used directly out of the toolbox. It would seem a genuine improvement for the daily work routine.

LEVER OR CHAIN?

Having opted for manual power, another choice remains: should it be a chain hoist, or a lever one? There are pros and cons for each. Chain hoists can lift heavier loads than lever hoists. On the other hand, “a lever hoist is more portable,” says William Hackett’s Burgess. There is less chain to fit into the above-mentioned toolbox, and to get tangled when pulling it out. “Lever hoists are better for pulling or tensioning applications.” A lever hoist can be used for pulling horizontally as well as vertically, which most chain hoists cannot.

Indeed, data from Columbus McKinnon seems to show that lever hoists are used more often for pulling – say to help tighten the securing straps on a load – than for lifting; chain hoists generally must be used for vertical lifting, or at least lifting limited to within a certain angle from the vertical. Chain hoists need two hands to work them; lever hoists can be operated one-handed. But with a lever the operator has to stand right next to the device and to the load, which can be hazardous – and the device has to be low enough for him or her to reach the lever from the ground; with a chain device a long length of pulling chain allows the operator to stand well away to the side, or to work a ceiling- or trolleymounted hoist mounted some distance overhead.

CAPACITIES

We have said that chain hoists can lift heavier loads. Ten to 15 tons is about the limit for lever hoists. The Yale C/D85 from Columbus McKinnon can lift 10 tons; the Tiger PROLH (which stands for Professional Lever Hoist) range goes up to 15 tons. William Hackett’s WH-L4 lever hoist includes models with working load limit ranges from 800kg up to 15 tons. Double safety twin pawls are fitted as standard.

SPECIAL ENVIRONMENTS

Most of the above are intended for standard, normal, everyday surroundings. But manual hoists, like powered ones, come in versions specially adapted for difficult or hazardous environments. Extreme temperatures are one such: in many regions – Scandinavia, Canada, the northern United States – hoists must function in temperatures below -20°C. Examples include assembly or repair work, for example of cable cars in mountainous regions, oil and gas production in the North and Baltic Seas, or simply work outside in winter.

At such temperatures some steels tend to brittle fracture, and to be much more vulnerable to shock loads. Fractures can occur suddenly, without prior deformation which might warn the operator of impending failure. Lubricants must be suitable for the low temperatures, or they too can promote failure.

Yale’s Arctic Edition chain hoists are customised for such conditions. They are made using appropriate materials, sold with appropriate lubricants and have been extensively tested down to ambient temperatures of -40°C. The tests include functional stress tests, endurance tests, fracture strength tests and impact tests. Consequently, they can be stored and used over a temperature range from -40°C to +50°C. They are available in capacities from 500kg to 10tons.

ATEX

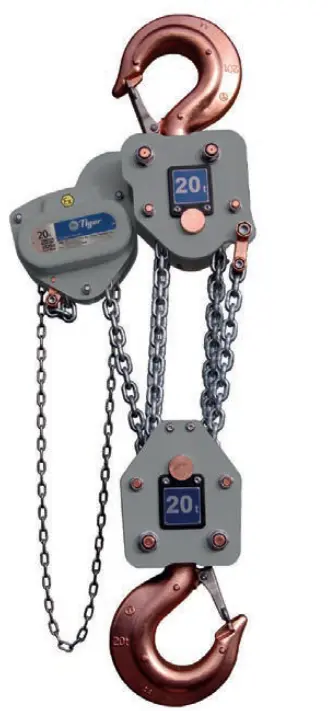

Explosive environments also need specialised and certified hoists. ATEXcertified manual and lever hoists are available from, among others, Yale, Tiger, Kito, Verlinde and William Hackett. Verlinde has the VHR EX sparkproof hand chain block in stainless steel, for capacities from 500kg to 20 tons. ATEX markings are Ex II 2GD c IIC T4 T+135 °C, which makes it suitable for Zones 1 and 2 and hazardous areas 21 and 22.

Spark-reducing adaptations include bronze coated hooks and a 70 μ layer of high-resistance RAL 9006 aluminiumtype powder coating. An overload limiter is standard; and there is an option to have the load chain as well as the hand chain in 316L stainless steel. Tiger’s SS20 lifts, as the name suggests, 20 tons.

CLEAN ROOM:

German manufacturers Rema has a hand chain hoist for clean rooms. The cover is chrome-plated; the side plates are nickel plated, as are the top and bottom hooks. Nuts, base discs and the hand chain are of stainless steel. The standard load chain is nickel plated but a stainless steel loadchain is an option, which makes the hoist suitable for use in the food industry.

OFFSHORE AND SUBSEA

Hoists for offshore and sub-sea use are also a specialised sector. William Hackett’s approach is explained by Burgess: “We have seen success by engaging with end users and understanding applications and environments where lifting equipment is used. We take a standard product, for example a lever hoist, and develop it for specific applications such as subsea. We have used surface treatments, different materials, and marine grease, and we also change the design of certain parts. We have mechanical engineers working for us who help with this product development.” We have already described its highcapacity ROV-recovery hoist. For offshore use it also has anti-corrosion combined hoists and trolleys; its SS-L5 offshore lever hoist was the first offshore lever hoist to be awarded DNVGL ‘Saltwater Immersion test ‘verification, which certifies that it can be safely used over a 21 day single immersion and a 31 day multi immersion period.

Tiger is also specialists in offshore and subsea. It has its SS20 corrosion resistant chain block, and the SS19 subsea lever hoist. Both include one-piece construction pinion gears and Tiger’s globally patented Quad Cam Pawl System. The SS19 includes a rotational inertia driven torsion switch brake and freewheeling system. This brake system was designed to counter known failure modes in commonly used mechanisms, which allow easy ingress of foreign particles into the mechanism that could affect hoist operation. This Tiger brake system is now a proven design with many thousands of hours of empirical evidence as proof of design and efficiency.

Working out in a gym is one way to develop your muscles. Why not instead put all that effort to useful work, by weightlifting outside the gym?